Interview,

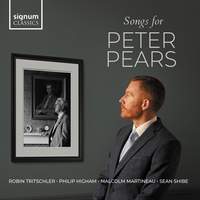

Robin Tritschler on Songs for Peter Pears

The programme includes Benjamin Britten's Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo, Geoffrey Bush's Songs of the Zodiac and Arthur Oldham's Five Chinese Lyrics (for which Tritschler is partnered by Malcolm Martineau), plus Lennox Berkeley's Songs of the Half-Light (with guitarist Sean Shibe) and Richard Rodney Bennett's Tom O’Bedlam’s Song (with cellist Philip Higham).

We spoke last month about Pears's extraordinary legacy, the qualities which made his voice and artistry so special, the challenges involved in approaching repertoire so tailored to a particular singer, and some of the recordings by Pears which Robin couldn't be without...

When did you first encounter Pears’s voice on record, and do you recall your initial impressions?

I have to start with Britten, because he and Pears have to be considered together to be able to talk about Pears’s singing. But when I was a student in Ireland, Britten was barely mentioned. His music was rarely played in Dublin for some reason, and certainly my singing-teacher didn’t encourage me to sing any Britten because he wasn’t really a fan of it. (I think there was perhaps a personal element there too: he never met Britten and Pears, but he’d go to conferences and visit Aldeburgh and find people talking down to anyone who wasn’t in the inner circle…)

It wasn’t until I heard the Serenade in an orchestral concert that I got interested; I went off and found a recording of Pears singing the piece, and I have to say that I was a little taken aback by the sound. I’m not sure there are many people who would describe Pears's sound as immensely beautiful, but what grabbed me was how incredibly striking it is. It’s like all the great voices: if you hear Margaret Price or Callas, you instantly know it’s Margaret Price or Callas, and the same goes for Pears. There’s such personality to the sound.

I sang the Britten Canticles and other bits and pieces before I came to London, and when I got there I was suddenly exposed to a lot of his songs; I remember going to the Royal Academy library and being astounded by how many songs he wrote for tenor, because at that point I hadn’t quite figured out how much he was inspired by Pears and vice versa. It was such a symbiotic musical collaboration, and it lasted their whole lives.

Pears would have had a career if he’d never met Britten, no doubt…but singing what? All the folk-songs, art-songs and chamber music that he did would still have been a big part of it - but in terms of opera he’d have been singing far more character-parts, because his was not a voice that fitted into the traditional idea of what an opera singer is. So you have to give him a lot of credit for the roles that were written for that voice, not least because they’ve enabled so many singers with similar voices to have careers too.

Leaving his relationship with Britten aside for the moment, what was it about Pears that inspired so many other composers: his distinctive vocal qualities, interpretative artistry, personal charisma, or a combination of all three?

The thing that is striking about Pears is his absolute commitment to what he's saying – he so obviously believes in it. He, Peter Schreier and Robert Holl have a special ability to colour a strophic song in a way that’s so full of emotion and pathos. He can draw you in without ever pushing the voice out, and it’s a quality I’ve always admired. We’re lucky to have so many recordings, but I wish I’d heard him live: to actually be in the room and experience the weight of expression and feeling which that sound carries must have been extraordinary.

The programme here spans several decades of Pears’s career: do you get a sense of his voice changing as he aged and composers responding to that, or was he something of a vocal Dorian Gray?

As he got older his technique improved enormously, and Britten played a big part in that. It’s interesting to listen to the Michelangelo Sonnets (from 1940), because even that early in the relationship Britten obviously saw his potential: the songs are quite heroic, but you also need the ability to float through some very long phrases. Peter Grimes comes five years later and that’s heroic too, as is Aschenbach in Death in Venice - and Pears was singing those roles in large opera houses late in his career. The voice got really big as he aged; it grew from this thin thread of sound that could project and carry this music over a very large orchestra.

And aside from all of that, he was a most wonderful actor: Grimes and Aschenbach could hardly be more different characters, and he absolutely inhabited both of them. If you watch the video-footage of him as Grimes, he’s unrecognisable as the man who stands up in evening-dress and sings a lovely Schubert song.

Speaking of being recognisable, how accurate do you find the infamous Dudley Moore parody of Pears (and Britten's folksong settings) in 'Little Miss Britten'?

It just goes to show that Pears was perhaps the most famous singer in the world at that time. He and Britten had toured everywhere and there had been so much music written for him, so the voice was instantly identifiable – if you were going to pick a classical singer to parody then he was the obvious choice. And Dudley Moore does it very well! It’s not super-flattering, but you immediately know who it is.

Britten obviously knew his voice intimately (and much ink has been spilled on how he responded to it in his writing), but do the other composers focus in on different aspects of it?

All of the composers who wrote for him played to his strengths, which is true of most composer-singer partnerships. We know that Pears very much liked to sing certain pitches: he could sit in that zone of E flat/E/F at the top of the stave all day, which certainly isn’t the case for most of us! That’s one technical thing I have focused on, but you can’t become obsessed with it. I remember Philip Langridge saying to me years ago that you have to endeavour to not sound like Pears in this music; that’s very difficult, because some of those phrases are just written for that voice to sing in that way, and you have to find a way to make it work without strangling yourself or changing the essence of the music.

But you do have to break away, because I don’t think Pears would have wanted anyone to ape his performances: he understood that making music has to be honest and individual. That’s why Jon Vickers’s recording of Grimes is completely different to Pears’s (or anyone else’s) - not better or worse, just different. There’s no ‘right’ way.

Other than the Michelangelo Sonnets, most of the songs here are relative rarities on record – how did you go about tracking them down, and is there more repertoire out there which deserves to be better known?

The idea came together backwards, because I came across Geoffrey Bush’s Songs of the Zodiac first: I was doing a programme about fables for a recital at Wigmore Hall, and I’d read about these songs in a book by Graham Johnson. I searched up the publisher and they printed me a score and sent it off; it’s only about 14 pages because the songs are only about a minute long, and on the top it said ‘In memoriam Britten and Pears’.

I’ve really taken to the songs of Lennox Berkeley over the last few years, and that was another piece of the puzzle; I did a set of Housman songs a few times and discovered that only one of them had been recorded (by Anthony Rolfe Johnson). I read more about them and started putting the story of Britten, Pears and Berkeley together…Britten had shared The Old Mill in Snape with Berkeley and planned to travel to America with him in 1938, but instead went off with Pears. That was when the idea of songs that were written for or dedicated to Pears took shape.

There is more music out there, probably enough for a second disc: there are songs by Elizabeth Maconchy, several pieces by the British/South African composer Priaulx Rainier and Alan Bush’s Voice of the Prophets, to name but a few. But for this album I knew I wanted to include some songs with other instruments and that led me to the Songs of the Half-Light which Berkeley wrote for Julian Bream, another person who commissioned a lot of music: he would go around begging composers to write for the guitar, and he created an awful lot for the repertoire.

I learned Richard Rodney Bennett’s Tom O’Bedlam’s Song on a week’s notice when I stepped in for a festival with Steven Isserlis a few years ago; it wasn’t the best performance I’ve ever given, but I thought it was extraordinary music. Pears knew Richard Rodney Bennett, and he commissioned the piece – at some point he wrote a lovely letter to Bennett saying ‘…if ever you want me to sing anything you may write, I will always be happy to do so - provided I can!'. It’s by no means an easy piece to master but it’s really a joy to sing, and the way Philip [Higham] played it was amazing: I remember when we sat down in this very room for the first rehearsal and he was just bang-on!

Thanks for introducing me to the songs by Arthur Oldham, who was a completely new name to me! What's the story behind his relationship with Britten and Pears?

I discovered those songs years ago when I was putting together a programme about Brittish [sic] music: I was so pleased with myself for making up that word, but years later I was reading Pears’s travel diaries and there it is! Oldham was Britten’s only student for a time; Britten and Pears recorded some of them, and I would think that Britten played a part in them being published by Boosey & Hawkes.

I found the music in an American second-hand bookshop; it’s the most expensive score I’ve ever bought, but it was worth it. They’d obviously been performed by Britten and Pears several times before they were published, because the score in Pears's library has a handwritten note saying ‘In deepest gratitude for so many wonderful performances’: this is the copy which he actually presented to them!

What might feature on your personal Peter Pears playlist, if we look beyond music which was written specifically for him?

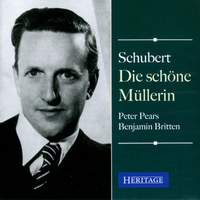

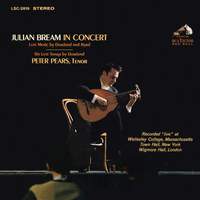

I would have to include his Schöne Müllerin, which I think is astonishing. There’s a tenderness and vulnerability there, and yet when the miller makes his final decision there’s a turn of tone: suddenly the sound has a bit more iron in it, and it’s extremely moving. I would also include his Dowland with Julian Bream, because of that special ability to pick out words in strophic songs. There’s a lifetime of understanding literature and texts behind those tiny shifts in colour.

I’m going to cheat and include some Britten (and I’d have to insist on the video as well), because I can’t leave out the War Requiem from the Royal Albert Hall. That last phrase of the Agnus Dei just breaks you, and I can hear it now: it’s one of those pieces that haunts you, and Pears sounds absolutely fantastic in it. Oh, to have been in the hall that day…

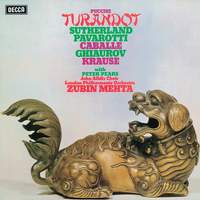

Personally, I think I'd have to slip in his cameo as Emperor Altoum on Zubin Mehta's recording of Turandot...

Oh goodness, yes! Every single voice on that recording is instantly recognisable - Sutherland, Pavarotti, Caballé - and Pears is not lost at all in that company. That’s how great he was. I’d love to have met him.

Do you know many people who did have the pleasure of his company?

You can’t be a song singer and not come across lots of people who studied under him or did classes at Aldeburgh. I’ve sung a lot with Iain Burnside and Graham Johnson, who met him at different times in their careers. But I’d have liked to have formed my own impression.

I’ve never had the same yearning to have met Britten, funnily enough: I don’t think I’m smart enough to have been able to talk to him, and I get the sense that he was quite lofty! About ten years ago I sang The Prologue in The Turn of the Screw with the late Steuart Bedford conducting, and I remember him sitting there with no score saying ‘No, that’s not written: that should be a quaver rest. Wait, there’s a pause there…’. I remarked on how great it was to work with someone who knew this piece inside-out, and he said ‘I had to - Ben insisted’.

Robin Tritschler (tenor), Philip Higham (cello), Malcolm Martineau (piano), Sean Shibe (guitar)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC

Peter Pears (tenor), Benjamin Britten (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC

Julian Bream (lute), Peter Pears (tenor)

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC

Joan Sutherland (Turandot), Luciano Pavarotti (Calaf), Montserrat Caballé (Liù), Nicolai Ghiaurov (Timur), Peter Pears (L'imperatore Altoum), Tom Krause (Ping), Pier Francesco Poli (Pang), Piero De Palma (Pong), Sabin Markov (Un mandarino)

London Philharmonic Orchestra, John Alldis Choir, Zubin Mehta

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC