Interview,

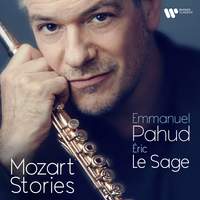

Emmanuel Pahud on Mozart Stories

We spoke to Emmanuel about falling in love with the composer in childhood, the art of transcription and the evolution of the flute since Mozart's time.

In the promotional material for this album, you describe Mozart as ‘the reason I became a musician’ – when did his music come into your life, and when did you first perform it in public?

I was five years old when I heard Mozart's music for the first time - without knowing it, because I'm not from a musical background. The music came from a neighbouring apartment where a musical family lived. I was humming this song that I liked in the hallway one day when the neighbour saw me and told me: 'Oh, that's Mozart's Flute Concerto that you're singing!'. I had picked it up from the neighbour who was practising it for his examination. So I asked him, 'Can you teach me Mozart's Flute Concerto?', and that's how it all started. Ten years later, after winning the Belgium National Competition for Young Artists, I was performing the piece with an orchestra on stage for the first time. That is when I decided it's not just for fun, this is the thing I want to do. I want to become a musician.

How much do we know about Mozart’s attitude towards the flute?

Mozart wrote a lot of beautiful music for the flute: the quartets, an early set of sonatas different from the ones I just recorded, plus the concertos, and the opera The Magic Flute of course. It was an instrument that he encountered at various stages in his life: in Salzburg, then in Mannheim, and also in Paris where there was a lot of instrumental music being written for woodwinds. It was there that he wrote the Flute and Harp Concerto and the Sinfonia Concertante for winds. So his relationship with the instrument was like for any composer; if he were alive today he would write for new instruments, composing with electronics and mixing with hip-hop and that kind of thing.

The flute was quite an established instrument when Mozart started his career. But by the end of his life, which was relatively short, things had changed. The clarinet was a new instrument, the horn was developing a lot of steam, and new techniques that pointed the way to the Romantic era had also begun to emerge. So I guess had he known the modern flute that we're playing nowadays, he would have written a lot more for the instrument. But at the end of the day, I love his writing because it's so vocal. Whether he writes a piano concerto, a violin concerto, an opera, or a symphony, it's always about vocal lines. This kind of singing music somehow appeals to the human soul, and it lends itself so beautifully to the flute in particular.

Did any of Mozart’s friends, colleagues or patrons influence his writing for the instrument?

Most of the sonatas I've recorded for this latest album were written by Mozart at the time he was also writing the flute quartets and the flute concertos. It was a time in his life when he visited Paris twice. His mother was based there because she loved the Paris lifestyle, much more than the Salzburg lifestyle, where his father had stayed. [In France] he discovered a lot of literature for winds and orchestra, for wind instruments and piano, and chamber music with winds. It was something that was specific to the French instrument school: not just the French flute school, but also the bassoon and oboe etc.

The conservatory in Paris was founded around this time, and the 'French Mozart', François Devienne, who was himself a flute player, taught there. Devienne wrote a lot of music, and organised public concerts where for the first time people could go without being from the aristocracy. It was truly music for the people, for the first time. These things that Mozart was encountering in Paris were life-transforming. He was actually not just influenced, but was also picking up a lot of this information and transcribing it into his own music.

We have to remind ourselves that Mozart is not just a part of a museum exhibit; he was a person living with other people, and they had a lot of influence on each other. He was playing contemporary music, for his contemporaries.

How much has the instrument itself evolved since Mozart’s time, and what are the challenges involved in performing his music on a modern instrument?

Well, the instrument itself has evolved of course from the wooden keyless instrument to a metal instrument with key-work, but there's also an acoustical evolution going on inside. The bore is different, and therefore so is the projection and the range of expression and dynamics of notes; just like other modern instruments, it's much larger. If you explore the palette of the modern instrument carefully, you can identify the colours, articulation and dynamic range of as an evolution from the classical flute that Mozart had at his disposal.

In the days that he was writing, the flute was an evolution of the traverso Baroque instrument, a little bit brighter in the sound and a bit more agile in the articulation. But it was considered to be one of the powerful instruments: it was the instrument of Frederick the Great, so it had something royal and poised to it. There was a lot of literature written in the previous generation too: the Bach family and Quantz wrote a lot for the flute. The modern flute can certainly expand on this palette.

There is also another thing to consider, which is the art of transcription when you're approaching literature written for other instruments. Back in Mozart's time you would just play any tune that took your fancy on your own instrument, often for the entertainment of your friends. This is something that was really common and there was nothing very special about it: it's just like simply playing the music you love on the instrument that is your own.

What is the history of the transcriptions on the album? Were they made with Mozart’s knowledge?

There were two sets of publications of six Mozart sonatas. When they first came out Mozart sold the rights to different publishers in different countries. There were Hamburg, Austria and Paris editions, and both the Hamburg and Paris editions were published as a set for both flute and violin, so it was done obviously with his agreement. Whether it was an agreement for money or he was involved in the transcription, we can’t be certain, as nothing is documented.

I decided to stick as much as possible to the original violin part in my approach to the works, because the modern flute of today can stick closer to the original violin line, and in its relationship with the piano part. Whenever I need to divert from it, then I take over the right hand of the piano part and the piano takes over the original violin part: for instance, if the range dips too low for the flute then we temporarily swap voices but keep the original music. This was quite an important principle for me: not to recompose Mozart but simply to adapt the original idea in a very minimal manner.

What other technical issues are involved in translating these sonatas from violin to flute?

Well, the biggest challenge for a flute player is breath-control, because we are the only wind-players who play on top of our instrument. All the other ones have more resistance, playing through a reed or a mouthpiece that's very small and therefore requiring more air-pressure, but releasing less air. For us flute players, the embouchure is open, just like for a singer; therefore we need to breathe more often, and sometimes the instrumental lines are so long...

But this is where Mozart is a genius because he is such a great lyrical, vocal composer in his writing. The phrase is always singing, always ringing, and there's a natural pace to it. If you breathe properly in the beginning, you actually can manage your way through the whole phrase. Sometimes you might have to disguise some of the breaths, and there are some spots to do this (for example where you play the same note as the piano), but the idea is to take as little away as possible from the original written line. On the contrary, you add the warmth, the mellow expressive tone of the flute across its range: that is something I find very vocal and expressive, and it allows this music to settle beautifully in this format.

Do you feel that all of the violin sonatas would transfer equally effectively, or are there special qualities about these works which lend themselves particularly well to the flute?

Not all of the violin sonatas can be served equally well by the flute because of the range or the fact that there's too many double-stopped chords, but the four I selected are gems. I could have picked another two or three sonatas, but those [on the album] together also display four different kinds of expressions in four different times of Mozart's life - even though they're not very far apart in terms of years, Mozart's life is so intense and dramatic.

When he writes the E minor sonata for example, his mother has just passed away while he was visiting her in Paris, and you can feel this endless sorrow and anger at the same time, which makes it a very special work; it sounds more like Schubert than Mozart, actually. Then you have the B flat major sonata which is to me like the spring weather we're enjoying right now. It puts me in mind of the Beethoven Spring Sonata: it has a similar kind of line in the piano and the flute in the beginning, and a very similar expression and pace.

Those are very beautiful examples of what Mozart can write. The C major sonata is very festive, even joyful in its opening. Whether you're familiar with classical music or not, it's just something that gives such immediate pleasure. In the G major sonata which I picked for the end (composed after the others he wrote in Vienna), you feel that Mozart has a lot more authority in his writing. It doesn't display so much virtuosity, but just the sheer beauty of the line and the turns in the expression, the depth of the simple melody, and the art of variation with the piano in the second movement is something that Beethoven would develop for the next decades - it is really a path leading to the art of writing sonatas.

How does playing these sonatas compare to performing Mozart in an orchestral setting, such as in your experience with the Berlin Philharmonic?

I've been playing both as a soloist and as an orchestral player for the last thirty-five years, equally in terms of number of concerts a year. Many treatises on orchestration quote a lot of Mozart - how he orchestrates or how other contemporary composers orchestrated - and the flute is always linked to spirituality. There's always something transcendent about the way he uses the flute (rather than the oboe or clarinet) in his symphonies, operas and concertos, and I try to preserve that quality in the sonatas as well.

Emmanuel Pahud (flute), Eric Le Sage (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC